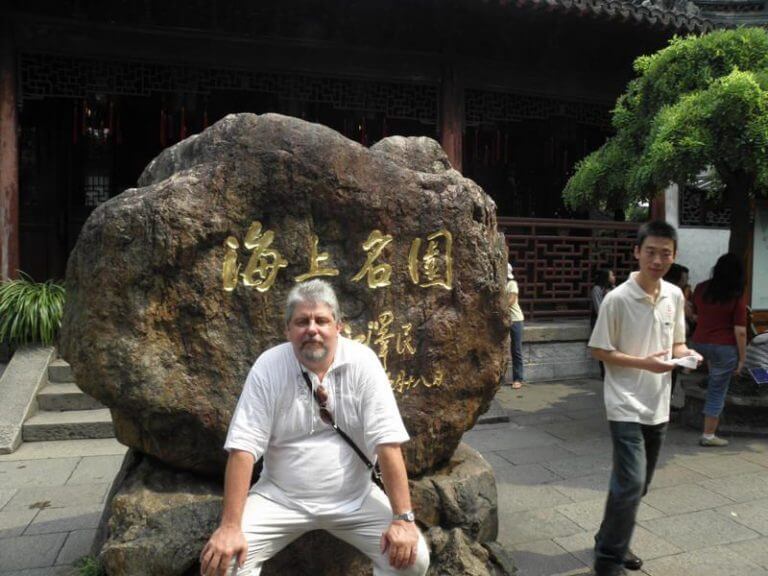

To visit Georgia in the Caucasus was one of the wildest adventures of my life. The hosts wanted to show us best of their hospitality. It included spontaneously scheduled excursion to some long-lost part of the country via bad roads through the mountains, headed for an unknown destination. In one little town the organizers left us and went to make some further arrangements.

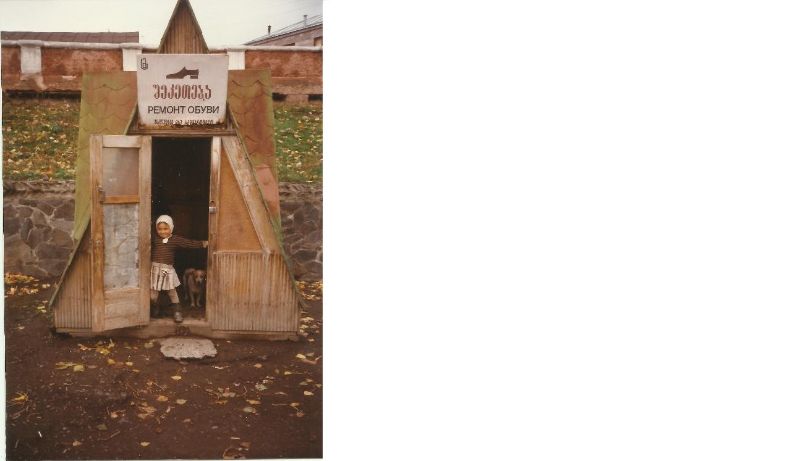

While waiting in some uncertainty as to what would happen next there was only one relaxing activity: taking photographs. We got out our automatic tourist cameras in the belief that we were spending our time usefully. We were particularly attracted by a nearby shabby wooden hut with the inscription – SHOE REPAIR. It wasn’t as interesting as the little girl and the little dog on its doorstep. They were both filled with childish curiosity when they saw us. We had taken a few photographs when, from out of nowhere, we heard Russian, spoken with a Georgian accent.

„Where is this Slovak?”

Why this unknown local should pick me out as a Slovak is a mystery I‘ll never be able to explain until the day I die. But in hope of a reasonable explanation I told him it was me.

He was one of the men also seen in other countries whose lives are passed huddled in little groups on streets in towns or villages. They talk, drink tea and, very attentively, pay attention to what’s going on. They do not look scary at first sight, but just they are ´opinion-making´ guard of any such street community. They will check you right away and if they would find you improper, the best thing you could do is to get lost as soon as possible. Based on this knowledge, my discussion with the unknown, unshaven man in rags started in the worst possible way. He came up to me, looked directly into my eyes, and asked in a loud, provocative voice, „Why did you photograph the cripple?”

I knew I was in trouble. In the hut with the SHOE REPAIR sign there might be a cripple – it’s normal in this craft. I didn’t see him; didn’t know he was there. But it was pointless to apologize. The man was absolutely certain that he was well within his rights to teach a foreigner a lesson and he knew, as I did, that he could rely on the solidarity of his street companions. Cripples and children are untouchable in every country. Woe betides any foreigner who makes such a mistake – as I had, however unwittingly. As it happens in these moments, those who could have helped me stood around silently in anticipation of how this impromptu drama would conclude. The unknown man’s acquaintances started to form a circle around me and cocked their ears for what was to follow. Every word was important. And I realized that I should speak about anything besides cripples. If I did, I would give him the chance for a dissertation on the arrogance and insensitivity of foreigners. I began carefully.

„You know, my dear friend.” In a desperate effort to think of something, I looked at my suede shoes and found sudden inspiration. „I photographed this shoe repair shop because back home we don’t have such shops anymore.”

„Are you serious?” He looked at me in surprise, but also with suspicion. He knew that I was pushing him off the mark by moving to another subject.

„Absolutely serious. Imagine: we produce such terrible shoes that they’re not worth repairing. They’re only made of imitation materials, and we just throw them away when they’re worn out.”

„Really?!” the man exclaimed with delight. It always pleases these opinion-makers of the streets to find out something from foreigners, that gives them a feeling of superiority.

At this moment they become hospitable and patronizing, convinced that you are worse off than they are. „You’re in a poor condition.”

„Yes, you’re right,” I eagerly agreed.

„Where is the world going?” he continued. But for a moment he didn’t want to let go of the possibility of a quarrel and started to censure me.

„When you take photographs, why don’t you photograph something that is really nice?”

He made a sweeping gesture around the square, which didn’t have anything especially nice about it. Thanks to this gesture, however, I saw that the circle of the curious was leaving out of boredom. I had won, but had to continue to stoke his pride with strategic compliments.

„I’m waiting with shooting for your beautiful mountains,” I assured him.

„Oh yes, our beautiful mountains,” the man echoed. He looked around for a moment, as if to assure himself that they were as beautiful today as every day, and then, with very practical tone, added: „I live nearby, come for vodka.”

When I came home I revealed this story, from great strife to a happy ending, to my wife. She wasn’t interested in my rendition of the story, nor in the powers of my shoes.

„Those terrible old shoes you’ll wear into eternity. You could buy some new ones!”

„New shoes?” I just took them off and said angrily, “These are the last examples of honest, handmade, indestructible shoes.”

I pushed them under my wife’s nose to prove my point. All-knowing, she shook her head, and before leaving me with my naïveté, she remarked, „Then look closely at your indestructible shoes!”

I looked at my beloved shoes and I almost had a heart attack. They were split completely open at the soles. When I stood in front of the Georgian shoe repair shop and had this war of words with the unknown man these shoes had to have been in similar shape. But I didn’t surrender.

At the shoe repair shop in our neighborhood they immediately dismissed the idea of fixing my shoes.

„We haven’t done these kinds of repairs for ages. We only repair what we can glue or sew together. Try downtown.”

I tried unsuccessfully a few repair shops downtown. In the last they were very patient with me. The woman behind counter took the shoes into the back of the shop and returned with a veteran shoe-repairer. He took them, expertly pulled apart what was left of them, and offered his condolences:

„New soles are needed, but we can’t do it. Twenty years ago we had to burn our good, old shoe-repairing equipment. In the communist times we over-produced shoes so much that repair became uneconomical.”

I remembered this utopian idea, but now we have capitalism again. Or not?

„Nice shoes,” he said, and gave them back to me pityingly. „Today they don’t produce shoes of this quality. And in this country no one can repair them. Maybe only …”

„I know,” I said suddenly. „I know where they can repair them.”

I went home and placed my beloved suede shoes on the shelf. One day I‘ll just have to go back to Georgia…

From a book (see in E-book form here) by Gustáv Murín: Svet je malý/The World is Small – collection of travel stories in bilingual Slovak–English edition, SPN Publ., 2012.