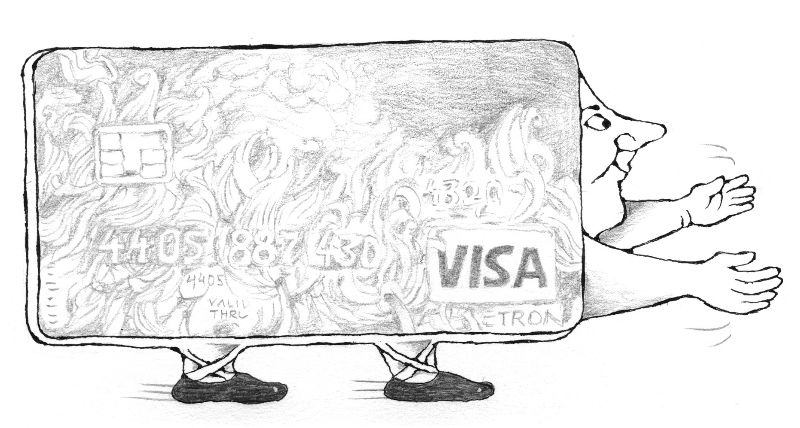

I am the enthusiastic owner of a VISA card. Anywhere – in Mexico, India or all of the Baltic States – it gives me an unusual feeling of a financial safety and security. But this very comfort led to me being punished.

That punishment was meted out in a country thousands of kilometers from home. The first warning had came in Kuala Lumpur when I needed to pick up some money from a bank-teller in the local supermarket called Sogo. I routinely punched in my little abracadabra that makes the machine disgorge cash. And nothing. The ATM returned the card. After that I remembered that my card has changed annually and a new PIN had been given to me. I suddenly had a terrible doubt about whether I had made a note of the new PIN. My great hope was in the little notepad that I always have with me. The new PIN was there. I tried again, and again the card was returned – this time with a warning signal. The situation was serious. On the next attempt the ATM would eat my card, and I’d be completely naked. I studied the numbers in my notepad again. Because the PIN number was recorded by my terrible handwriting, it was entirely possible that I had made a mistake. Finally, I enlisted my travelling colleague Karol to help to decipher this rebus. After a short consultation, we found a combination of numbers that held my last chance. And it worked.

But yet, on the first day of the conference, this state-of-the-art technology betrayed me again. Here in Serdang, on the university campus, the ATM wouldn’t accept even the new PIN code that had worked in Kuala Lumpur. Once again I faced the hazardous prospect of having the ATM eat my card if I tried repeatedly to make it work. It was morning and a line-up of Malaysians, with their undoubtedly working credit cards in hand, stacked up behind me. My Malaysian colleague from the conference’s board advised me to give up for the moment because my lecture was to start in ten minutes.

So the conference has started. I was physically present but, by rights, I wasn’t. I was to give a lecture before an international forum of my scientific colleagues, all of whom could sit there, satisfied with the knowledge that they had paid the registration fee for the conference. Only I had had no chance to do so. Due to my faith in technology, I hadn’t taken my iron reserve of US dollars. All my money was to be conjured up by a little piece of plastic. During the lecture I thought about all kinds of near-catastrophic possibilities. The money that I needed to pay for the registration fee (not to mention accommodation and food), I couldn’t get without the credit card. My Slovak colleague Karol (conservative about new technologies) couldn’t help because he had his money in a sock, and his sock wasn’t big enough for both of us. I didn’t know anyone else here – this is the disadvantage of international meetings held at exotic places. It made no sense to call home. No one could have picked up money from my VISA account when I was here in Serdang. My destiny was to persevere.

After my lecture, the conference organizers provided me with another Malaysian colleague and a car. We went to all the other ATMs on the university campus and, again, nothing. However, my Malaysian colleague didn’t lose hope and offered to visit the nearest bank. The teller smiled, took my card, and begged my patience. The wait seemed infinite. The only actual topic of conversation with my unknown Malaysian colleague was the unreliability of credit cards and the related technology. It was better to say nothing. The head clerk of the bank who politely but resolutely returned my card broke our silence. He said they couldn’t help me in any way. I was traumatized.

I hope you never feel that one of the pillars of world globalization is crumbling. I was forced to ask the heretical question about what, in fact, a man could rely on in this world. What is certain in this world?

My Malaysian colleague looked sympathetic but couldn’t help me. After the unfruitful visit to the bank, he was bereft of ideas and merely looked to me for new avenues to explore. I had some. The ATM I used in Kuala Lumpur belonged to Malaysia’s biggest bank and it now appeared to be my last chance. I asked him if they had a branch somewhere near. They did.

In front of the branch of this bank was an ATM. I went there immediately and, like an illusionist before the disbelieving eyes of my Malaysian colleague, I went through my routine. Instead of a rabbit from the hat, I waited for money to be dispensed. After the usual crunching sounds of electronic cogitation, I heard a squealing, terrifying sound as my card was ejected. I went inside the bank in total panic. I was desperate – get me my money! My appeals ranged from every decent approach to hints of an international scandal in the making. Without a prospect of prosperity I could change from a respected scientist with a dollar account to a suspicious impostor without a penny in my pocket.

I couldn’t stand the prospect of waiting in line, so I asked my Malaysian colleague to call for the supervisor. After a short time we were sitting in his office. He was big, fat, phlegmatic and sweaty, but polite. He listened to my story, took my VISA card, and carefully examined it from every possible angle. Then he typed some numbers into his personal computer and the information was biffed off to somewhere. He wasn’t satisfied with the result. I started to sweat, which in Malaysia hot weather is not difficult even under normal circumstances. But I was sweating two times more.

The supervisor remained silent. Once again, he checked the data on my card and asked me for my passport. Then was interested about the bank, which had given me the card (it was futile because the name of the Slovak bank had no chance of making any impression in international banking parlance). Then he grabbed the phone and called the head office in Kuala Lumpur.

The whole time my Malaysian colleague sat beside me and tried to keep my spirits buoyed with an optimistic look. From time to time he spoke with the Malaysian banker – either trying to help me or trying to expose an international con artist. I was alone in the middle of an unknown country and had only a plastic connection with home and my money that was failing by any step.

The phone connection with Kuala Lumpur broke down every moment. The Serdang branch office, meanwhile, was restful, with no one hurrying – and I could have swum in my own sweat. Then I remembered triumphantly that I always save confirmation from banks. I checked my pockets and found the receipt from the ATM in the Sogo supermarket. Full of new energy and hope, I gave it to the banker. He politely looked at the sweat-stained paper. It didn’t make any impression on him. He returned it to me. He called again.

After the connection broke down for the second time and for the third time he repeated the information from my VISA card, he enthusiastically raised his eyebrows. My chance had come, but it rested on one crucial question.

He leaned toward me confidentially and asked:

„What’s your mother’s name?“

„Who?“ I said, not understanding.

„Your mother’s maiden name.“

„But my mother never had any VISA account before she was married – and not today, either,“ I said.

„But you must have given it when you applied for this card.“

I hated questionnaires, but at this moment I was happy and said it with great eagerness. He had me write the name just to make sure. At this moment, it was curious to hear my mother’s name in Malaysian pronunciation. But it worked.

I got my money, breathed more easily and, with pleasure, shook hands with my Malaysian colleague and the bank representative. When I walked out to the unbearably hot pavement I finally understood. Who else if not the world’s bankers know that everything in this world can be uncertain. Only Mum is always certain…

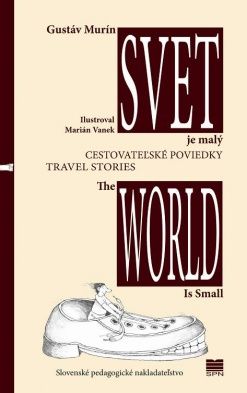

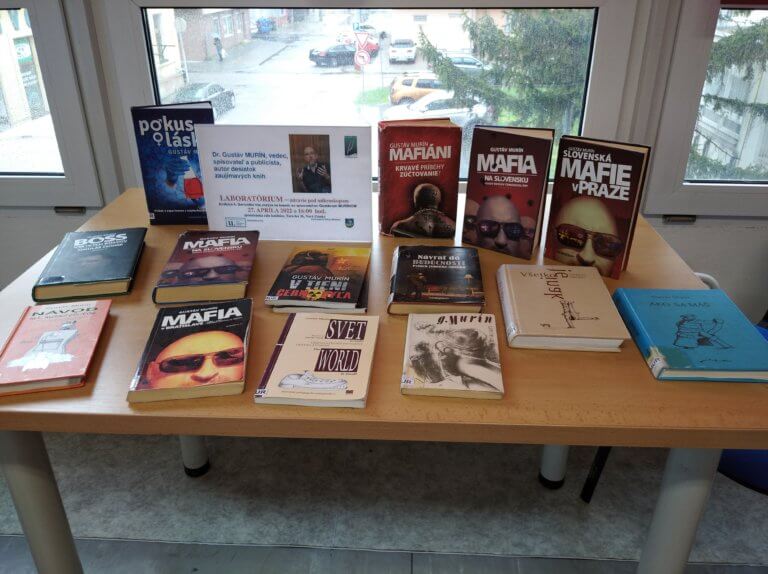

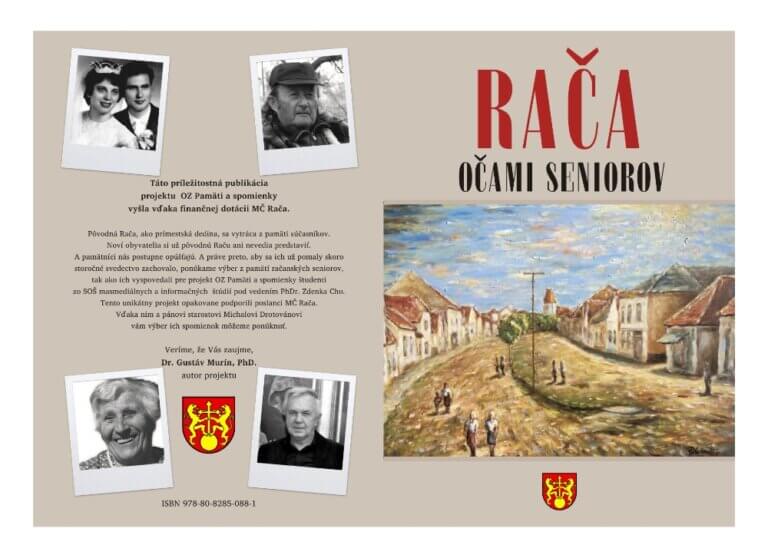

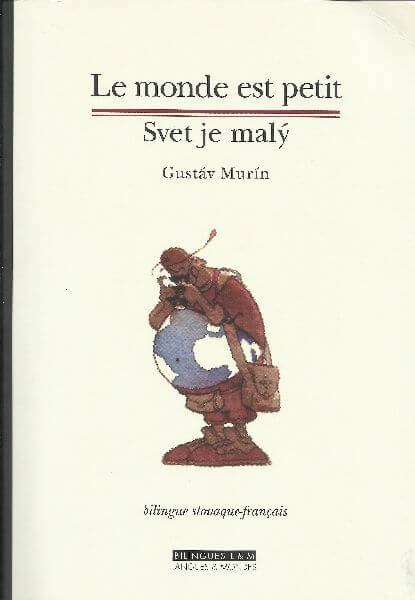

From a book (see in E-book form here) by Gustáv Murín: Svet je malý/The World is Small – collection of travel stories in bilingual Slovak–English edition, SPN Publ., 2012.