The Spanish siesta is famous and well respected at their Universities too. They go for lunch and a siesta home. I spent this time alone with my amateurish attempts at sandwiches. In my soul, I apologized to Slovak subsidized, university cafeterias for all my jokes and ironic notes about mass expenditure on animal fodder.

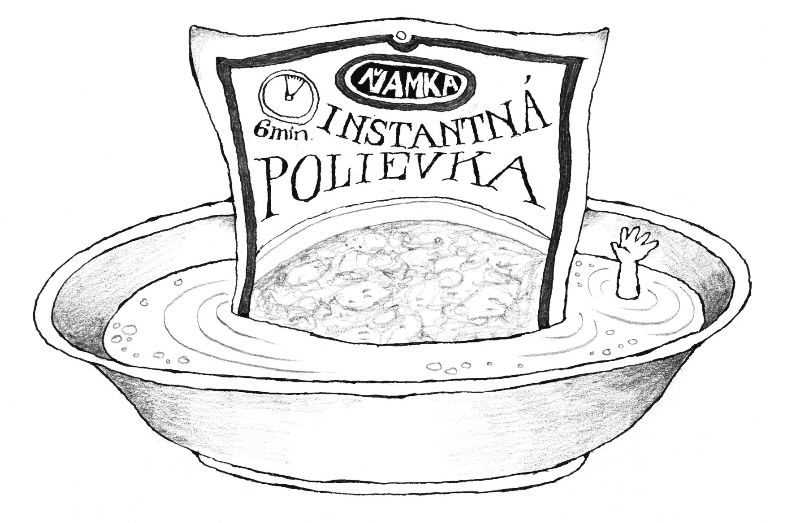

And every evening the same thing was waiting for me at home – an instant soup. The explanation is simple. I can’t cook and all I was able to prepare was a soup from a sack. I had a routine to make these soups better. No matter what kind of soup it was, I added cooked potatoes and a little pieces of cooked wiener. I had no money to go to the restaurant not only because of the paltry stipend, but also because of the exorbitant costs of health insurance. I had to save money if, God forbid, something would happen to my notoriously problematic teeth. And for my travel plans across Andalusia. Last but not least to save something for family gifts too. From this kind of diet, I not only lost weight, but also I had dreams about food – mostly about meat.

I had had similar experiences on other grant excursions. When I was in Prague shortly after graduating from University, from time to time monthly payment from my grant would come late and I had to borrow money from older colleagues.

My distressed dinners were the smallest possible baked sausage with mustard at a stand at Wenceslas Square, and so much bread. Once I was even saved by the Soviet political leader Constantin Chernenko. He died on the day when I was at the bottom of my finances but a lot sooner I had bought a ticket to the theater. Because there was a state funeral, the theater was canceled and my money was refunded. So, instead of going to the theater I went to Wenceslas Square for the usual sausage-dinner. The problem with my Spanish stay was that I was on a mono-diet. Those three months I lived on 36 varieties of the same instant soup.

At the end of my stay I found a free week for my dream trip to the glorious attractions of Andalusia. I wanted to see everything and, because I was short of money, I lived in the cheapest hotels, traveled on domestic buses and walked every city I went. I walked across Cadiz and Algeciras, I popped in to Ceuta on the African coast, to British Gibraltar, walked across Malaga, and with the same enthusiasm I walked through the historical sites of Granada. Map in my hand, I walked around the marked tourist destinations until I saw a church that wasn’t on the map. I was surprised that even my tourist guide overlooked this historical spot. I was enticed by the long, quiet mass of people moving into the church. Out of curiosity I followed these quiet figures. They didn’t say hello or speak to one another. We went together into an anteroom where these people waited patiently in silence. Before I could reveal that I was a stranger in this society, the door opened and a monk appeared and invited us all inside. He went out of his way to assure me that I was one of them so I went in.

In the big refectory hall, I became aware of what was going on. We were the second shift in a big, clean banquet hall where lunch was being put on for homeless people. I was both hungry and curious, so I stayed. I didn’t betray myself as a stranger. I decided to ask no questions and simply mimic everything that they were doing. It wasn’t difficult in this quiet society, where no one was paying any attention to anyone else. They were focused on the food alone.

Thick fish soup with white-bread rolls distended my ascetic stomach. The dish was filled to the brim, and seconds were immediately provided on request. My companions automatically asked for more. I watched them very carefully.

They didn’t look bad or fulsome. Two of them at our table were wearing something resembling suits – a little threadbare and not ironed, but approximating suits nonetheless.

Then the main course came – it was also fish with potatoes and a salad. The portion was huge but some of my quiet friends had no trouble asking for second helpings. The other diners finished it quickly and then brought out some empty bowls from home. The third helpings were transferred to these dishes to be eaten at home later.

We left as quietly as we had arrived. At the door as we were leaving everybody got a package with a big portion of bread, which ordinarily would have sufficed for a week for my laboratory surviving. Besides the bread there were chocolate and oranges. If I understood it well, for the local homeless people this was a daily portion.

After walking two streets, I discovered that I was in trouble. I couldn’t move. In the nearest church, I slumped into a pew – for completely secular reasons – and sat completely still at least for an hour. I could hardly move or breathe. After two and a half month on a soup diet, this lunch for the homeless was more than I could handle. I was ready to burst. While I tried to find the power to move again, I had time to recall a saying of one famous scientist: „Science is offering bread and butter, but without jam.“ It seems to me that this man of wisdom never dined with the homeless in Grenada. And had never heard about instant soups…

From a book (see in E-book form here) by Gustáv Murín: Svet je malý/The World is Small – collection of travel stories in bilingual Slovak–English edition, SPN Publ., 2012.